Seems everyone these days is getting into the game of providing frameworks for thinking about blockchains and trying to convince others that their definitions are the correct definitions. Into that marketplace of metaphors, I provide this entry.

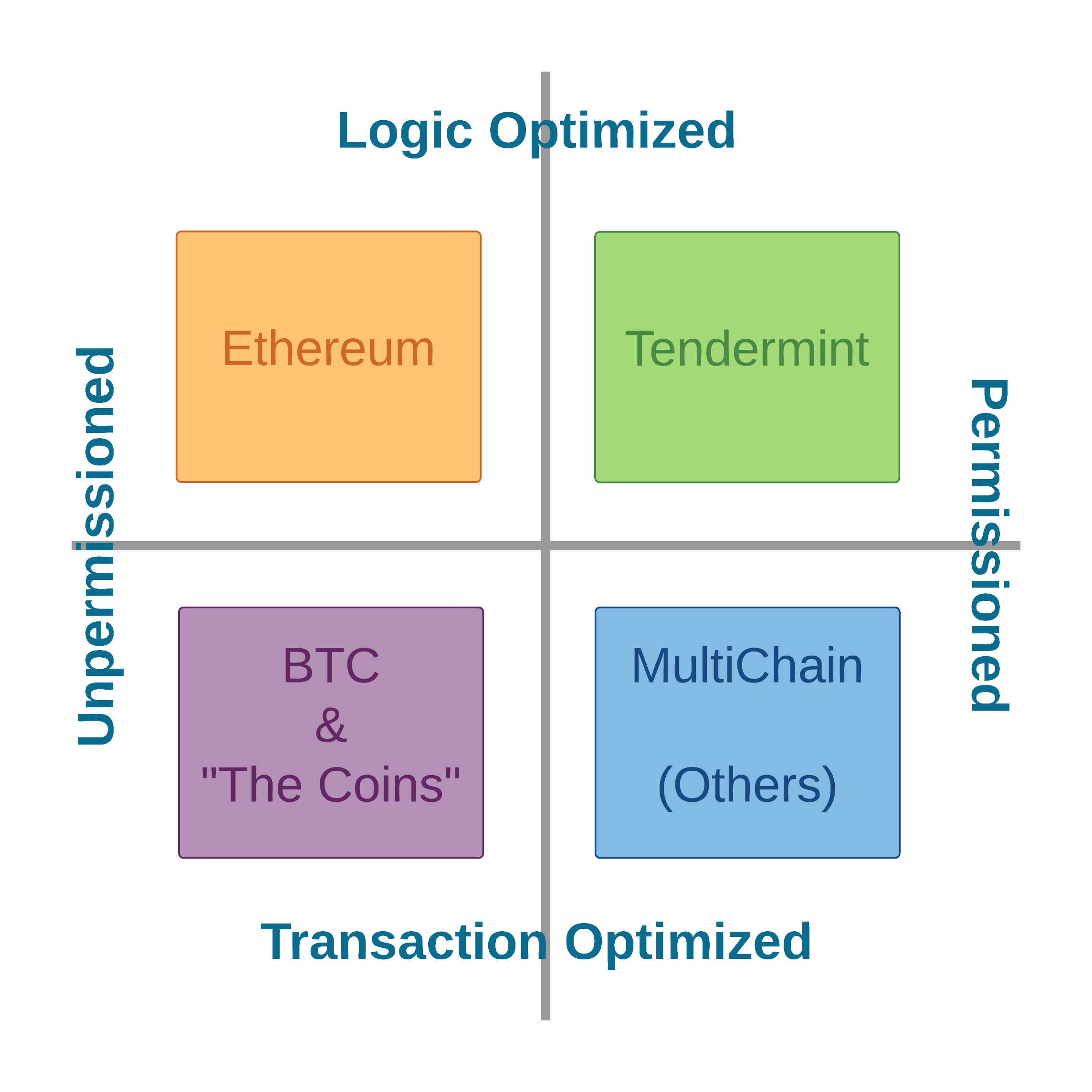

When I look at the development of the sector generally, what I see is roughly two “types” of blockchains and within each of those types, two “flavours” of blockchains. These types and flavours can be graphically depicted using two dimensions.

On the X axis of the diagram we can formulate a spectrum of permission-able-ness. These permissions are usually capabilities based permissions, meaning the permission is to interact with a capability of what the blockchain can do. Whether a blockchain design is capable of being put into permissioned mode or not is an important operational consideration for application developers (whether those are startups or enterprises). That permission layer may provide an advantage in censorship resistance (if it is absent) or in compliance risk mitigation (if it is present).

On the Y axis of the diagram we can formulate a spectrum of optimizations. These optimizations are roughly binary at this point, although we fully expect that it will be more of a spectrum that will develop over time. On one side we have transactional optimized blockchains. These are the chain designs which have been developed to support digital cash and are now being permissioned and built to provide clearing and settlement solutions. On the other side we have logic optimized blockchains. These blockchains have been optimized to provide an arbitrary framework for running small scripts which are saved onto the blockchain (which we call “smart contracts”).

In total, my mental diagram looks like this:

While the above may not perfectly capture all of the blockchains in existence, I think it does a fairly good job of providing a framework for placing most of the space into some easier to consume boxes.

The Optimization Spectrum

On the lower half of the quadrant we have blockchains which give application developers a clear and efficient way to verifiably track title transfers in a distributed environment. Whether these blockchains are permissioned or unpermissioned, they are a good fit for application developers seeking to build transfer mechanisms, clearing and settlement, and provenance applications. In other words, they’re really interesting property registers. These blockchain designs – to some extent or another depending on the blockchain in question – do provide some limited logic capabilities (bitcoin, famously, has its multi-signature capacity which operates in a similar area to logic). However, they really have been optimized to track movement of title over “property” from one node on the network to another.

On the upper half of the quadrant we have blockchains which give application developers a clear and efficient way to verifiably track business and governance process logic in a distributed environment. Whether these blockchains are permissioned or unpermissioned, they are a good fit for application developers seeking to build complicated business process mechanisms. In other words, they’re really interesting process auditors. Similarly to transaction optimized blockchain designs, they have capabilities of supporting verifiable title transfers, but they have really been optimized to run arbitrary business logic.

The Permissioned Spectrum

On the left half of the quandrant we have unpermissioned blockchains. These blockchains lack an access control layer and as such handle anti-spam and consensus via purely economic mechanisms. We may not like to have to pay a bank a fee to update our address in their database, but if our bank operates on a public blockchain that’s basically what we’d have to do in order to overcome the necessary anti-spam protections (and other protections) which have been put in place to protect these unpermissioned blockchains. These blockchains are the best solution for censorship resistance. If someone needs data to exist forever in a rock solid vault of math and environmental degradation, then public blockchains are the place for that data. Public blockchains also have public governance mechanisms, as we are finding out with the blockchain debate. Whether the increased uncertainty which is the current state of the public blockchain governance oligarchy is a good or a bad thing remains to be seen. Lastly, public blockchains have been designed to provide the backbone for a variety of applications. That means that they were probably not well suited for any one type of application. Depending on what application one is seeking to build this may be a benefit or a detriment.

On the right half of the quandrant we have blockchains which are capable of being put into a permissioned mode. Generally speaking, permissions can be made fully public, or use whitelisting to control who can validate batches of transactions, who can add functionality to the blockchain in the form of smart contracts, and who can transact with the chain. These chains are not susceptible to external attack by unknown actors because the clients running the chain will reject blocks from not-whitelisted nodes (if the client is running in “permissioned” mode for a particular blockchain in question). These chains also may have slight performance advantages over public blockchains because they are only dealing with the functionality required for that chain rather than all the functionality for all of the people for all of the time. While permissioned chains have some upsides, they also have some downsides of course. The downsides include a reduction in censorship resistance, and an increase in responsibility for application developers (who now have to also have some operational responsibilities).

Hope that helps your own mental framing of the state of blockchain technology.