This article is Part 1 in a 1-Part Series.

- Part 1 - This Article

Smart contracts give us increased veribiability over business processes that cut across stakeholders. But that is, admittedly, an abstract concept. Over this series of posts I will be working to elucidate what such systems look like from our perspective.

When I speak with clients I am constantly noting that there are roughly two ways to leverage smart contract technology. On the one hand you can identify business processes which you would like to automate but have been unable to with current technology (because, as we know, traditional business process automation stops at your organization’s glass doors) and automate those processes in a cost reduction effort using smart contract technology.

But reducing opex is only one way to satisfy corporate duties to maximize shareholder value. The other hand, to me, is equally important. Namely, what new profit centers can open up for service providers if others adopt smart contract technology?

While it is interesting and important that various verticals (finance being the most vocal at the moment) are looking at how they can leverage smart contracts to reduce middle management and back office costs which are indicative of their individual vertical, smart contracts are actually much more interesting when looked at from a slightly different lens. Namely, how can individual firms band together to open up new potential profit centers using smart contract technology.

One Problem With Streaming Services

There is an indelible tension within the commercialization of art between an artist usually having comparative disadvantages as to how to commercialize their art and the artist not wanting to lose control of how that commercialization happens. This tension has played out over history and is not particularly new. The rift between global artists such as Taylor Swift, or Adele, and streaming services (Spotify being the most prominent) is only the latest incidents in a long history which this tension evokes. Before that we had label wars, ticketmaster wars, agent wars, and on and on.

The challenge which current musicians face with music distribution chanels is that there is a huge variety of services in which they can place their songs, such as:

- Youtube

- Spotify

- iTunes

- Google Music

- last.fm

- rdio

- and many more

If you are an independent artist and wanted to distribute your music on just the available streaming services, not to mention physical sales or radio distribution, you’d either have to sign up for each of these services individually or you’d likely use an aggregator service of some kind. Aggregator services ease the amount of maintenance an artist must do as to their profile, about page, tour dates, current releases, back catalogue, etc. Yet they do so, gasp, for a fee. These aggregator services are prototypical middle-humans, but ones who actually solve a problem which many, many independent artists I know have, and because of that they thrive.

If you are a signed artist rather than an independent artist, it is still likely that your label will use an aggregator service of some kind, although there are typically different aggregators which labels use. Labels, of course are also middle-humans. They typically provide financing for the recording of an album, as well as marketing and distribution support once the album is ready for release, and – at times – support during a tour. Obviously, in return for this, the label will also take a cut of proceeds.

But rarely is the making of music a purely solo endeavour. Usually there will be additional stakeholders involved in the creation process of the album. Session players, engineers, producers, and song writers all will typically be given “points” on the album or a given song on the album.

On top of all this, individual artists will usually have individuals who will be “personal” to the artist or band. Namely, agents, business managers and the like.

All in all, we can roughly break down the carveouts that artists typically will have to account for into three major categories:

-

“Artist level” cuts. Examples:

- Business managers

- Agents

-

“Album level” cuts. Examples:

- Labels

- Producers

- Engineers

-

“Song level” cuts. Examples:

- Session players

- Song writers

The above list is only meant to be illustrative rather than authoritative. Obviously it is only meant to cover the carve-outs/payouts of value which extend from the streaming service itself through the complex network of entities and humans involved.

The amounts and types of payouts will vary greatly based on a complex matrix of contractual obligations which an artist has put in place to support the creation and commercialization of their art. This is very complex because each individual artist, album, and song combination will have its own unique set of cuts which will be taken from whatever value flows to the “artist” (or, as Spotify’s quite pleasant artists portal calls it, the “rights holder”).

So, from our point of view, there is a real challenge here, which essentially collapses into an accounting challenge. And its a challenge which we think that smart contracts can help to overcome.

The Smart Contract Backed MVP: Stakeholders

Just because a smart contract backed system could help here, does not mean that it will. Actually building this will require much more than a simple idea. For the purposes of this post, let’s set aside some of the political resistance within large industrial actors and assume that we’ve successfully engaged with them as to the benefits of a smart contract based approach to solving this problem and then lets see how we would actually build it (which is really what this particular post is supposed to be about).

Who do we need involved in the pilot?

- A Streaming Service

- 1-5 Labels

- 5-10 Independent Artists

- An auditing firm

- The Streaming Service’s Bank

Getting the streaming service is obvious. We’d think you would want some labels involved in the MVP as well. The larger and more influential the better, but that is by no means a requirement as smaller labels will likely have more flexibility and be more likely to embrace innovation. We’d also think you’d want some independent artist involved to make sure that whatever was built was not too focused on the problem set which is specific to labels but also included the problem set which independent artists face. On top of that you would likely want an audit service involved to perform internal auditing services in the form of running a node on the network and validating what was happening within the smart contract system.

Finally, and perhaps most controversial, we’d think you’d want to get the streaming service’s bank involved. Why? Isn’t blockchains all about replacing the banks? Not to us. To us, blockchains are about increasing the verifiability of business process which cut across stakeholders. If, for example, the bank used by the streaming service was one of the dozens of global banks who was experimenting with and using smart contract technology then the bank may benefit from such an experiment just as much as any other stakeholder involved in the system. This is especially true if the bank also was one of the growing number of banks who had identified that banking of the future involves the “Bank as a Platform” see also. As we will see shortly, the bank as a platform is very relevant to making this system operate in the current regulatory schema with the least possible disruption or opportunities for political challenges to growing the MVP into production.

The Smart Contract Backed MVP: Smart Contract Overview

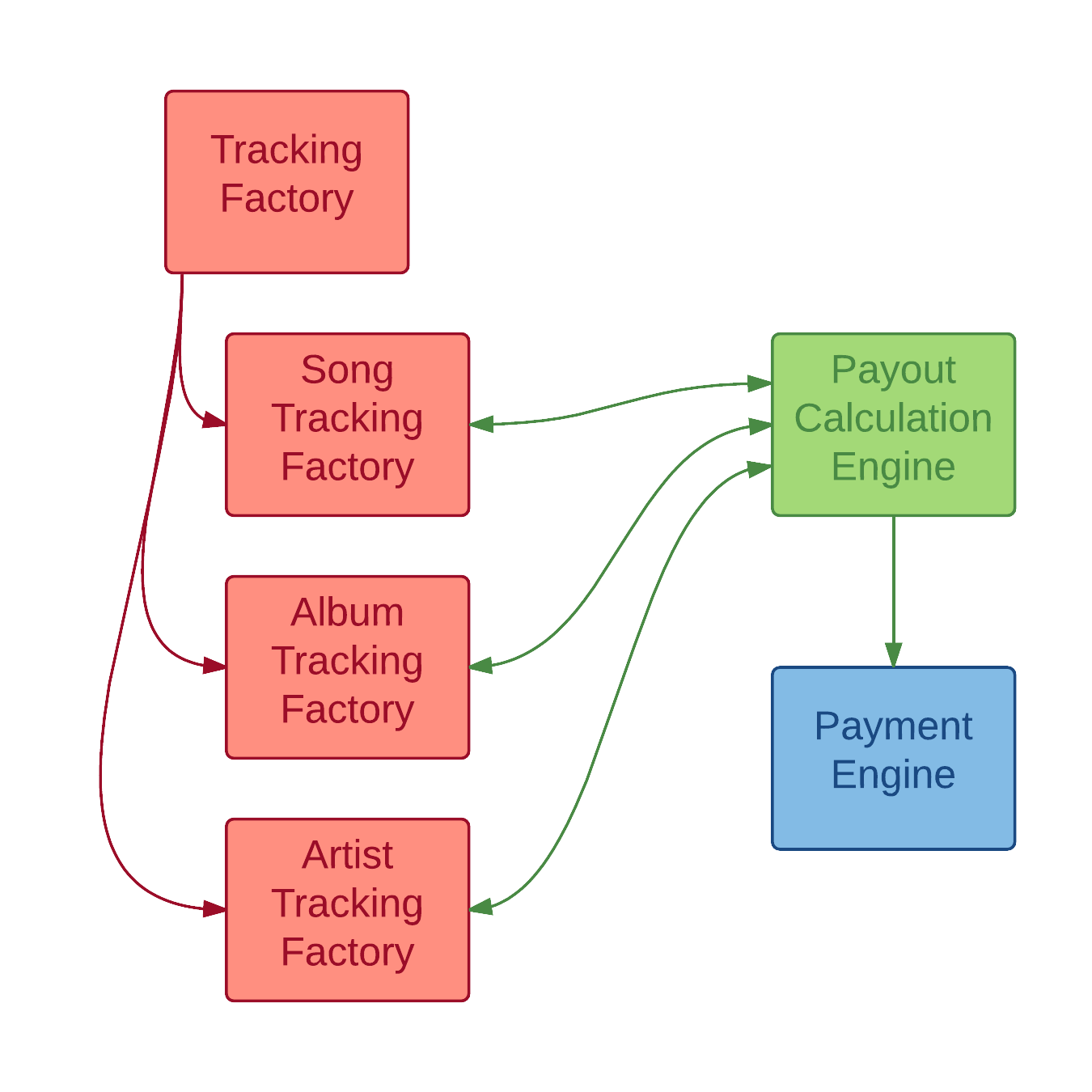

The most simple way in which to build the smart contract system, and the way we would recommend as a point of departure for the effort would involve two engines and three factories.

Before I detail what these do, I think it would be helpful if I explain a bit about how we think of smart contracts from a design and high level overview.

Understanding Smart Contract Factories

The general way in which I explain smart contract systems to developers coming from a web application background is to start with a typical database-model-controller-view web app stack and to say that, essentially, what happens in smart contract backed applications is that we collapse the database and model layers into the smart contract layer, build a middleware (controller layer) and then a frontend (view layer). This helps communicate how we think of smart contract backed applications. It isn’t a perfect analogy as indeed there are differences, but it gets us within the range of proper thought models.

If we adopt an object-oriented paradigm for smart contract backed applications then we need a way to instantiate and track objects. In the Eris paradigm, which we’ve been working on for something like 18 months now, how we track objects is to use smart contract factories. Factories, in how we build smart contracts, perform two functions.

First they act in a similar way to how Class Definitions work in object oriented programming languages. In other words we use them to instantiate objects. Generally we instantiate single object contracts by using factories to create a unique contract which has the parameters that were included when the instantiation transaction arrived at the factory. To break this down a little bit, a general “new” function is built into a factory contract which has required parameters that must be sent along with the function call. What the “new” function generally does is to wrangle those parameters and to create a new, individual object contract, which has all of the required parameters.

Second, we use factories to map “where” the contract is to a unique identifier of some sort. So if we have a system of bonds we can us the ISIN number of the bond, or if we’re tracking songs we can use the UUID from within the streaming services main database as the unique identifier (usually human or machine readable and linked to some other system, such as the streaming service’s database). This unique identifier is the key in a key:value store which is kept within the factory. The value of the key:value store is the address where the individual “object” contract resides.

This allows us to “get at” any individual object contract by sending a query call to the factory (which is in a more stable and well known address within a smart contract network) with a particular unique identifier (say, the UUID of a song from the streaming service’s “normal” database) and get back the address of the individual object contract.

Understanding Smart Contract Engines

On top of needing to track objects, we generally need to build system level functionality which will be guaranteed to (1) satisfy a particular interface and (2) allow us to plug this functionality into what objects “do”. To build this functionality into smart contract applications we use the idea of smart contract engines. These engines are generally, but not always, stateless contracts which are built to do one thing and do it well.

We generally build engines to satisfy an interface and register them with an overall tracker contract (which we, still, call a DOUG contract; n.b., we generally register factories with the DOUG as well, so any middleware seeking to integrate with the system needs to be given DOUG’s contract address and can “find” the rest of the system via DOUG).

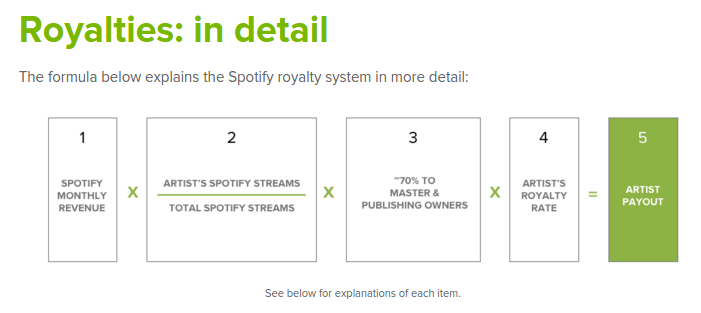

The engines, in this example, would be likely to perform the functionality of calculating the payout. By way of a simple example, Spotify has a fairly transparent formula for how it calculates payouts to artists; which at the time of this blog post looks like this:

(Photo credit: Spotify)

The payouts engine could in this example, be a transparent calculation agent of the set formula for the streaming service.

Bringing It All Together

So here is how it could look.

First, one would utilize the factory contract paradigm to establish mappings of Artists, Albums, and Songs. These mappings would be likely to include the various payouts and “points” (or percentage payouts) which would go to the various stakeholders involved in the process. Of course, there would need to be some mapping somewhere of the individual entity or individual’s payment details so that the bank could eventually send them the money. This would not be wise to be kept within the smart contract system itself but rather within the bank’s systems (why and how that would happen I will save for another day).

These factories (in red in the above diagram) will allow the payments engine to identify, based on the unique identifiers from the streaming service’s “normal” database of songs, albums, and artists (a reasonable assumption, but an assumption that the streaming service establishes unique identifiers for such things).

Second, and primarily, one would build a payments calculation engine (in green in the above diagram). This engine would be the primary recipient, of, say, a daily dump of songs that had been played. The contract would then parse that dump, query the individual object to determine what the relative cuts were for all the stakeholders, and then send along a series of payment instructions to a payment engine (in blue in the above diagram) based on whatever formula was negotiated between the streaming service and the artists they were distributing content for. Again, for an example of what this formula would look like, see Spotify’s quite transparent formula linked to above.

Third is the payments engine. This engine would generally receive a unique address (or other identifier) which would, within the bank’s systems be mapped to real world payment instructions within the jurisdiction (ACH bank details, SWIFT payment details, SEPA payment details, whatever). Along with the unique address where payment was to be sent would be the amount to be sent. This engine could be a very simple tracker engine. While engines are usually stateless, this engine would likely have a state. The idea being that the calculation engine would determine who and how much payments would be sent and would send these transactions into the payments engine. The payments engine would then collect these and then the bank, using whatever real world payments rail it deemed, would then make the payments in the real world from the streaming service’s current account (or whatever they currently used to pay artists). When the payment had been made then the bank would notify the payments engine of that and the transaction would be recategorized somehow from a “pending” state to a “paid” state.

Perhaps to close the loop then this would all be registered back into the object contracts.

The Smart Contract Backed MVP: Building the Chain

In addition to the smart contracts, one also needs to build a blockchain which will work behind the scenes to keep this whole system cryptographically verifiable. For this system we would build a permissioned blockchain design (there is no real need to run this on a public blockchain unless one wants to run the payment rails via the token of endogenous value within that blockchain; however, should one do so, one would be severly limited due to liquidity and capitalization limits which even the largest blockchains when matched against the scope of real world commerce). We would build a network of validators which could be run by, for example:

- streaming service (with roughly 25% of the stake);

- streaming service’s bank (with roughly 25% of the stake);

- streaming service’s outsourced internal audit firm (with roughly 25% of the stake);

- a consortium, or election of representatives amongst the labels involved in the system (with roughly 12.% of the stake); and, last but not least,

- a consortium, or election of representatives amongs the independent artists involved in the system (with roughly 12.5% of the stake)

These validator nodes would work to keep the system in sync. There would also be other accounts, probably for the developers of the streaming service, and the rest of the system would be kept not behind a VPN but in the public sphere so that it would be transparent for all involved in the system. On a daily basis, the only nodes which would really need to “interact” with the system would be the streaming service (which would need to sign and verify play counts and send those to the payments calculation engine) and the streaming service’s bank (which would need to sign and verify when payments had taken place). The rest of the nodes could be given permissions to “see” the system but not to actually interact with it, thereby ensuring the authenticity of the system. Over time, of course that could be relaxed based on the various permissioning capabilities of the blockchain base that had been used.

The Smart Contract Backed MVP: The Benefits

The benefits of this system are a few:

- simplified accounting for all that happens;

- reduction in lag time for all stakeholders to get paid; and

- more flexibility for the streaming service should it need to establish various payout calculation engines for various artists (we may not like that Taylor Swift gets a better deal that Wax Fang, but if we want Taylor Swift on Spotify perhaps that’s the market doing what markets do).

Over time, more complex additions to the very simple MVP could be added.

Conclusion

Decentralized purists will get their hackles raised by this post because it is no where near a “pure” decentralized application. We “used” established bank payment rails rather than a decentralized cryptocurrency to facilitate the value transfer within the system for one thing. In our view this would be an easier system to sell to a major streaming service than one that included a “purely decentralized” payment rail such as bitcoin. Yes, we are still using banks, but we are also leveraging banks while also helping banks to understand what their role could look like in a future where smart contract backed systems are part of their “bank as a platform” play.

The other thing which will raise the hackles of decentralized purists is that this application as currently overviewed does not get at a number of other problems streaming services must face, such as music discovery, gaurantees of play counts, decentralized content distribution, and other things. Those are all interesting problems, and indeed a music streaming service built by decentralized purists could get at some of those challenges, but likely not all of them. In any event, those problems were not among the problem set I was trying to overview within this post.

This post was more about giving folks a bit of a feel for what types of systems Eris will be working towards over the course. An exiciting year, it will be!

(Photo credit: CC-BY-SA: bangdoll)